Remedies of our ancestors: Returning to Palestine

a living archive

My Dear Reader,

While researching Palestinian ancestral practices, I attended community events in Chicago, IL, and Amman, Jordan and met Palestinians of various ages. Some expressed a desire to connect with their grandparents’ practices and some expressed their appreciation for the remedies. Others recognized that they embody ‘ancestral knowledge’ through our conversation. One interaction that is seared into my mind was with Frank Chapman(1), a legendary Black community organizer in Chicago. He said: “Oppression is a fact. What I do about it is what matters.” Frank explained that liberation movements heal because they challenge what appears to be possible. This moment was one of many that transformed the way I make sense of the liberation movements.

My research started with an investigation into how Israeli pharmaceutical corporations exploit Palestinian natural resources and ancestral remedies. It grew to focus on Palestinian ancestral healing practices. I came to realize that I could not make sense of how the Israeli government restricts Palestinian bodily movement, such as foraging and farming, without illustrating the significance of these movements. Their significance lies in reading them as expressions of self- crafting and freedom that refuse to comply with the structures of power that dictate a discursively narrow and rigid image of Palestine and Palestinians. When Palestinians prepare their land and remedies, their bodily movement articulates a powerful history of Palestine that is rooted in ancestral relations with a long history of repetition and knowledge production. Our personal narratives capture the human story of Palestine. It yields different imaginaries of the land and Palestinian social history.

This project curates a living archive, a tool, an emergent strategy2 in order to weave personal practices with collective organizing through conversations and interviews. I offer it as an intimate political and social space to share Palestinian histories, as an ostensible bridge between theory and narrative. I regularly asked two questions: “how did you heal? How did your caretakers heal you?” And followed with: “Where/how did you learn this?” I have so much yet to learn from our families, neighbors, friends, and plant relations, but I think we can begin with similar questions.

What emerges is a story of how the land of Canaan (what today is the land of Palestine) gave us life and continues to do so despite colonial and imperial violence. The archive and analysis presented here embraces Palestinian temporal entanglements, in which our pasts, presents, and futures are not hidden or cut off from one another. It is a place where we can live in the simultaneity of that entanglement. We cannot separate 1948 from 1912, the second Intifada from the Oslo Agreement, nor land enclosures, apartheid wall, checkpoints, and Gaza as an open-air prison, from international neoliberal economic structures. We hold intergenerational memories, stories, trauma, and ancestral practices.

May this archive encourage curiosity about Palestine. May it push readers to ask questions that challenge colonial epistemologies and build homes for collective healing and ancestral wisdom. This archive showed me what is possible, I hope it does the same with you. May this archive be a compass that guides generations of Palestinians towards a return home and welcomes generations of non-Palestinians as guests on this journey.

Until Liberation and Return,

sarah

(1) An interested reader can learn more about Frank Chapman and the Black Liberation struggle in his book (2019): The Damned Don’t Cry.

(2) Adrienne Marie Brown (2017, 2) defines emergent strategy as: “... ways for humans to practice being in right relationship to our home and each other, to practice complexity and grow a compelling future together through relatively simple interactions. Emergent Strategy is how we intentionally change in ways that grow our capacity to embody the just and liberated worlds we long for. [A]nd maybe, if I’m honest, it’s a philosophy for how to be in harmony and love, in and with the world.”

Recovering Remedies:

As I sat alongside elderly Palestinian women residing in Chicago, Illinois, I asked them: “what do you know about Palestinian folk medicine?” “We know the merameyeh for stomach cramps.” “There is also Yansoon.” “The other day I found a ‘attar’49 on 87th and Harlem and mashallah he has everything from Palestine. It reminded me of the ones in il Blaad.(50) I am going to go back to his shop if you want to come with me.” (Interview 8). They began conversing with each other and ended with: “We do not remember everything. Give us some time to think about it.”

The Arab American Action Network, a community-based organization in Chicago, Illinois held a community iftar,51 where everyone prepared different traditional dishes such as stuffed grape leaves, Musakhan, mashed roasted eggplants, rice with minced meat, and lentil soup. It was an intergenerational gathering of Palestinians from various Palestinian villages and cities. We sat down patiently to break our fast together with some water and dates, while other women rushed to begin prayer.

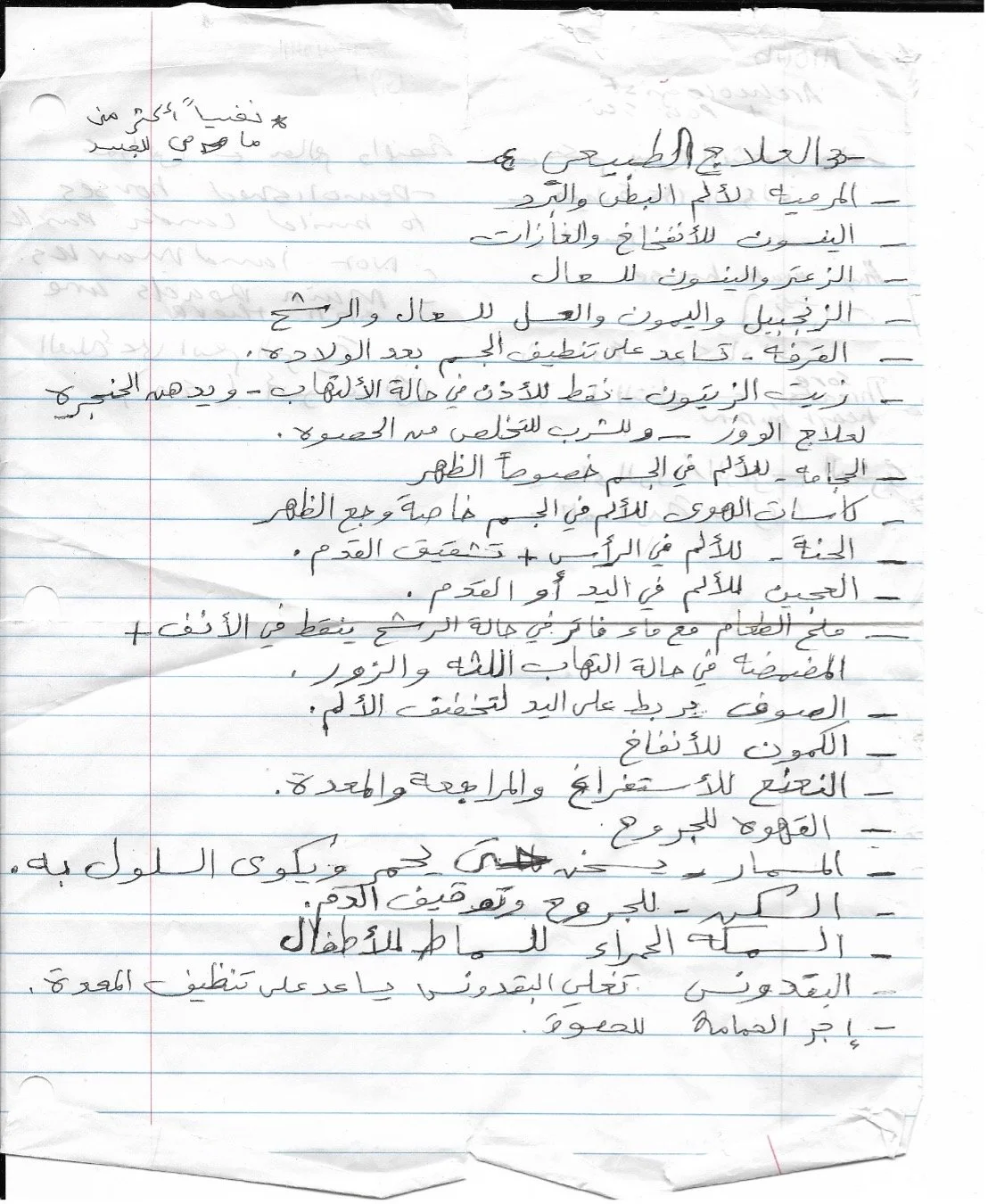

They returned with a handwritten list titled: “natural healing:”

image description: a lined paper with medicinal properties of herbs and plants.

Remembering Remedies…

“You should test the effectiveness of the remedies, so try these remedies yourself. Try each one of the remedies on the list and see what it does.” (Interview 8)

I responded: “I will. But I am also interested how we got these remedies as well as whether or not they are effective. It seems that these remedies are inherited generationally.”

“Well, yes not only that, but these were the practices of the people under different empires. The ruling powers in Palestine changed many times but the governed public remained the same. All these ruling powers of course controlled narratives and the narrators. But still if you go into any Arab household you will find almost the same spices and herbs.” (Interview 8).

Aroub shared with me. “My family and I were forced to leave in ’67 from Imwas to Jordan,” where Aroub studied political science and anthropology at Yarmouk University. “They demolished all our houses and built the Canada Park. They demolished the houses, but not the landmarks. That is why you can actually trace where your house was. For example, the main roads are still the same and the village mosque is still there.” (Interview 8).

Ilan Pappe (2018, 167) concurred with this statement: “only one-tenth of the trees planted by the Jewish National Fund were species indigenous to the region. Nowadays Israeli environmentalists decry the destruction of the local ecosystem by the proliferation of European trees.” Despite Israel having built the Canada Park to indigenize the Israeli settlers while de-indigenizing Palestinians, Palestinians continue to embody ancestral practices. Aroub continued to share knowledge about cumin, sage leaves, rose water, and tea compresses to relieve a pink eye.

Halima’s Coffee Grounds…

As we conversed, other women at the community Iftar were curious to see what was on the list. As soon as Halima looked at the list, she exclaimed: “That’s right! My cousin once fell and got an open wound on his head. My mother quickly rushed to put some coffee grounds on the wound to stop it from bleeding. And it worked! I just remembered this. I don’t know how I forgot about it!” (Interview 8).

Halima remembers her mother’s act of care and unthinking reliance on ancestral knowledge practices. In this critical moment, both Halima and I learned (or remembered) that coffee grounds, or البن, are used like alcohol to prevent infections of open wounds. I understood that our act of sharing stories about ancestral remedies helped Halima and I resist the psychological erasure Palestinians often seem to feel. Our conversation, or what Scott (1990) calls the hidden transcript, “is a social product and hence a result of power relations among subordinates... it exists only to the extent it is practiced articulated, enacted, and disseminated within these offstage social sites” (Ibid., 119. Italics, my own.).

These social spaces “where the hidden transcript grows are themselves an achievement of resistance; they are won and defended in the teeth of power” (Ibid.). Since the disconnection Halima and I experienced is manifested as forgetfulness or disconnection in our psyche or sense of self, then it can be one site where we can overcome alienation and reconnect. Our conversation allowed both Halima and I to expose the roots of this disconnection; became excited as we began to make sense of knowledge practices we inherited. The list of remedies triggers a memory of when and where Palestinian ancestral knowledge is practiced. It is almost as if the knowledge is familiar but enigmatic. Interestingly, Halima traces the practice of when her mother rushed to apply coffee grounds on her cousin’s wound. Her act of (re)membering challenges the silences found in discourses on Palestine and Palestinians regarding embodied ancestral practices, and her disconnection speaks on the epistemic erasure of Palestinian embodied ancestral practices. Her mother relied on a healing practice derived from an ancestral knowledge system, which signifies a social history of Palestine grounded in relationality.

These ancestral practices can help Palestinians make a new sense of their world and history. Gramsci (1971) states that “power resides not only in institutions but also in the ways people make sense of their world; hegemony is a political and cultural process” (Pappe 2018, 165). The story of Palestinian folk healing allows for an emphasis on the temporal politics of healing; invites a creative lens of possible articulations of Palestine and its liberation, as well as, resists Israel’s political and psychological erasure. These articulations express freedom and autonomy in the midst of oppression because there is room to make sense of Palestinian identity beyond the occupation. They offer an alternative approach to tell life truths that can yield a kind of collective healing. When social spaces such as the community Iftar exist or are carved out, more space opens up for (re)membering, articulating, and practicing ancestral healing. In turn, that which gets articulated can move against the grains of epistemic erasure and political erasure. Halima and I are learning that social sites where Palestinians share their knowledge practices and embody them can exist as acts of return, connection, and collective healing both mentally and physically.

It is possible, then, to say that Israel only interrupts Palestinian ancestral knowledge and its praxis because Palestinians continue to practice ancestral healing knowledge in Palestine or the diaspora. Whether Palestinians are conscious of it or not, they continue to embody ancestral knowledge practices that frustrate colonial and imperial dominance. Ultimately, these knowledge practices reflect a way of life and being that enacts a politics of resistance. It shifts the Palestinian collective narrative to one which also harnesses a collective narrative of a future imaginary; anti-capitalist and anti-racist imaginary.